Emerson, Lake and Palmer

by Ian Dove

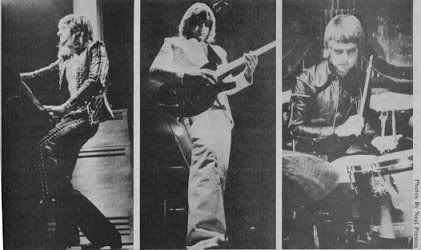

Keith Emerson was once a quiet reserved musician on stage, a fact hard to believe in 1974 when the focal point of Emerson, Lake and Palmer works with 13, count ‘em 13, keyboards, ends a concert by strapping himself on to one of them and revolving, still playing, like a human ferris wheel. It’s harder to believe when you consider all that amplification, those towers of power, that ELP carry around to project their distinctive music.

But quiet Keith Emerson was - back in the days when he was a semi-pro musician, working at music part time, and as a bank teller in Woking, England, full time. And bank telling is a profession hardly known for raving around or, even, throwing knives at Hammond organs, both of which Mr. Emerson has been known to practice. Keith was actually sacked by his branch manager for illegally playing jazz piano during his lunch break at a local pub. This event led to him trekking to London to work at music full time. Eventually it also led to Keith joining the Nice, a group that, now disbanded completely, settled into the same format, approach and line up as Emerson, Lake and Palmer.

Keith’s manager at the time, Tony Stratton-Smith (who now runs the Carisma [sic] label) recalls the quieter side of Keith Emerson: "When the Nice was first formed it was as a backing group to an American soul singer, P.P. Arnold who was then working exclusively in England. It was more or less a throw-away group.

“Keith would be hiding at the back of the stage, right in the shadows and behind his Hammond. Hardly anybody saw him but he had ideas and gradually the Nice’s part of the show, which was essentially to warm up the audience for Miss Arnold, started to become longer and longer. Miss Arnold permitted this and eventually it led to the Nice, spearheaded by Keith, taking over.

“And as a solo act Keith, I suppose, got nervous and worried about the music holding up by itself. He decided that somebody had to do something and this was where the quiet side of Keith Emerson disappeared. Probably forever.

“Keith decided he had to be the showman and so all the leaping about, standing on his Hammond organ, cracking whips and sticking knives into the instrument, started. I don’t believe he was actually into throwing knives at his speakers at that time. I don’t think he thought his aim was all that good and he needed more practice. That all came later.

“Actually the first real appearance of the Nice, the one that got them off the ground, so to speak, at the Windsor Festival in England, should have given everybody a hint of the wilder things to come. The band, more or less unknown, was booked in a large circus tent, and went on stage to an audience of less than a dozen, probably all relatives. Just to attract attention Keith let off a big smoke bomb outside and when people came running to see what the hell it was all about, there was the Nice, with Keith flailing a whip and rocking, in the literal sense, his Hammond, backwards and forwards.

“I think this episode had a strong - possibly overstrong - effect on Keith and on us all. We really didn’t think we could get this, somewhat complex, music across by itself - there had to be the showmanship. Keith had to come up front.” But now in 1974, six years later, despite the 200 separate items of equipment Keith, Greg Lake and Carl Palmer trundle around with them, valued at around $200,000, the group sternly maintains that their on stage presence has cooled down.

Says Keith Emerson mildly: “I think we can afford to exaggerate the music a bit.”

Keith is wary about defining Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s brand of European rock, preferring to use musician’s standard cop-out No. 1: "It’s music - period.” But he does react when people accuse ELP of just playing classical rock (that is rock with a stiff dose of classical music added, not Messrs Berry, Domino or even Haley).

“Not the correct description at all - I’m just as much influenced by jazz as by Bach. Our adaptions of classical pieces that we use in our concerts are not really what this band is about because most of the stuff we play in concert is our own material. If our rock is different from the usual variety you have to understand our roots. Most of the rock groups in America come up with the blues, that genuine American music, as a foundation.

“But we are from Europe and our heritage, if you like, stems from classical music which is really a lot more complex than the blues. I myself had around ten years of classical music, the effects of which I suppose I still carry around. I find that American bands have a looser approach to what they play - it sounds like jamming half the time, but that’s not for Emerson, Lake and Palmer. I suppose we could jam with the Grateful Dead, say, but I think it would be impossible for them to sit in with us because we believe in structure.

“That doesn’t mean that we're rigid in our music. We think it is very important to leave large segments in the arrangements where a musician can improvise and play as he feels which may be why you hear those odd squeaks of bebop, ragtime and old style boogie in our work. It may be because a lot of our music is tight and controlled that we have to let ourselves go. I’m sure that, for instance, a lot of Elton John’s showmanship is just a release from the intensity of his music, something to keep his feet on the ground.”

Emerson, Lake and Palmer are unique in one respect--they actually prefer playing large halls and even festivals. “This year we will play more festivals if we can,” states Keith. “Previously festivals have been something that we have avoided because they were usually so badly organized. But now we think the group has reached a stature where we can dictate the structure of the festival. And we have no problems with our sound.”

Greg Lake Interview

by Cameron Crowe

(Photos By Neal Preston)

Guitarist-producer-vocalist Greg Lake is the inconspicuous backbone behind Emerson, Lake and Palmer. It is his forceful bass, stabbing guitar and powerful dignified voice which perfectly set off the overwhelming virtuosity of drummer Carl Palmer and organist-moog genius Keith Emerson. In the following conversation, done in San Francisco during a stop along ELP’s recent tour, Greg speaks articulately of his role in one of rock’s most innovative forces.

HP: Where does Emerson, Lake and Palmer stand at the moment?

Greg: I don’t think we stand at any particular type of crossroad. In other words, I see us continuing along the same path we’ve followed from the start rather than reaching a point where we're gonna deflect one way or the other. Time has settled ELP into a direction.

HP: And are you happy with that direction?

Greg: Yeah. By that I mean ... not that we’re complacent, obviously, but we’ve set the direction of the band in as much as what our responses are within the band. We know each other very well, not only musically but socially, and the fact is we’re very happy to maintain ELP as a three piece band. We work well together. There’s no real reason to change the momentum of the way things are going.

HP: It’s surprising that you all get along so well off-stage.

Greg: I imagine it is. It’s a funny band, you know. It runs on a democracy. Unless all three of us agree on something, it doesn’t get done. In a way, it can hinder progress of a band because you tend to do less things. If everything has to be unanimous, not a whole lot gets accomplished in a short period of time. But whatever you do do, is done with togetherness and full gusto. Complete enthusiasm. That may be one of the reasons this band has become so successful. Politically, we’re very just.

HP: Is that the main reason for ELP taking so much time with their efforts?

Greg: Certainly that’s one of the major factors, but I wouldn’t credit that as the reason we take time. We take time because we want things to be very good. We impart high standards on ourselves and that generally makes it heavy going. If we’re not satisfied, we don’t record it or release it. We’ve thrown a lot of material away. Sometimes I wonder if it’s right, actually. A lot gets passed by ... material that should maybe be kept.

HP: Why is the album entitled Brain Salad Surgery when the actual "Brain Salad Surgery" tune is on the flip-side of a single?

Greg: I’ll tell you the story behind that. We basically had finished the album and had all agreed that it was what we wanted it to be. It was well-balanced with regard to each of our performances. and that is most important with our recordings. Yet we had studio time still left, so we dug out some of the tapes of things that we maybe jammed on for two minutes in between takes.

There were three or four tracks in there that weren’t really anything, but they were things that could be used ... good basics. They were very loose and that’s something that we’ve never actually put on record, you see. These tracks were very, you know, very disorganized ... brutish in a way ... and with our left over time we re-cut the tracks. “Brain Salad Surgery”, the tune, came from that. Then there’s “Tyrone’s Spotlight”. That’s a fantastic track, you ought to hear it. Really a basher. Heavy rock ‘n roll.

HP: But is that what you’re really into? Watching you during your acoustic set onstage, you really seem to be...

Greg: Getting off.

HP: Right. “Lucky Man” and “Still You Turn Me On” could easily be given the full ELP sound, yet you do them with just one guitar.

Greg: That’s very true. The first part of the show is just so full-force ... for me, it’s nice to just sit on a chair and play my acoustic. The whole fucking thing just stops for a little while and people can just sit and listen without being done anything with. They can enjoy just a simple melody without giving it a tremendous amount of thought. It’s just there to be enjoyed and it’s a nice, relaxing part of the show for me.

That’s the reason, really, that I haven’t got into orchestrating “Lucky Man” or “Still You Turn Me On”. It’s possible, of course, we used to do it with “Lucky Man”, in fact. But it’s better to just sing the tune with the guitar and just get up and leave. A little bit of warmth never hurts. Then Keith does his piano solo, which is very close to him, you see. It flows well. That’s why it’s there. It’s also principally the way I write.

HP: Do you consider yourself a prolific songwriter?

Greg: It’s all comparison isn’t it? I am quite prolific, although I tend not to be very productive because I’m very critical of what I write. Often I write very simple things and when you write basic tunes, they’ve got to be very good, ‘cause if they’re not ... they’re very, very bad. So I’m very choosy about it. Very choosy about what to let out. I mean, I’ve got lots and lots of songs that I haven’t done yet for fear of not knowing if it’s right. I wrote “Lucky Man” when I was twelve. I thought it was silly for a long time.

HP: Just think of all the hits you’ll be having ten years from now.

Greg: Right. It all works out in the end.

HP: How do you look back on that first ELP album?

Greg: The first album, ahhh. The first album was the egg. It was the egg of the band in which, to me, everything was in a delicate case at that time. It hadn’t actually cracked open and become a vibe yet. It was too early. The time when Emerson, Lake and Palmer began to make music as one was with Tarkus.

The reason for that was that we discovered in each of us a kind of percussive property. Keith is a very percussive keyboard player. I’m a very percussive bass player and, of course, Carl is percussive by the very nature of what he does. See what I mean? When we realized that property, that was the first time we realized the style of ELP ... if you can believe, in defining someone as having a specific style.

I think you can. I mean I can tell a Yes track immediately when I hear it. So that’s where our sound essentially comes from. Our first album was there, but it hadn’t yet become fruitful. While one of us was being percussive, the other may have been busy being melodic, you see. Which also is interesting, but at that point we were concerned with working out our foothold rather than embellishing upon it. Tarkus was a very important album and I think it shows. Then we recorded Pictures At An Exhibition and that had had about a year of development as a good piece for us ... so that had taken form as well and was encased in the style.

HP: Why was the first album successful? The band hadn’t been touring?

Greg: What really took place, I should think, was that the people who were into music at that point knew about Keith and myself and Carl as well. They knew that Keith was the mastermind of The Nice, that I was the bass and singer in King Crimson and that Carl was in Atomic Rooster and The World of Arthur Brown. They were aware that the heritage was a heavy one. They knew that there was gonna be a vibe there. That was the incentive to listen. So at least we had a listening audience.

The second thing was that “Lucky Man” was ... well, it just happened to be a popular song. One of those things. It was a hit tune, so that was another reason. Still another reason, and perhaps the biggest one, was that we knew what the fuck we were doing. When we came to America, we knew we had to lay down as heavy a show as we could. And we worked very hard to make our live act something that was theatrically, as well as musically, entertaining. So we considered what we were doing and plotted everything out. You see, we had the advantage of coming to America before. And we knew the rock concert audiences well.

We knew what we wanted to do. The reason that we formed the band really was that things were in phase with each other. It comes back to that agreement, you see, and we all agreed about what we wanted to do. Emerson, Lake and Palmer become very strong. We didn’t come on light at all. Most bands, when they come into America, try to suss it at first. And while they’re trying to suss it, people are saying 'I guess they’ll be alright in a year’. We came on like gangbusters from the start.

HP: And the key was experience?

Greg: Principally, yes. ‘Cause no matter how much good management, promotion, whatever, everybody does for you ... you gotta be together. You can't fool people. When you get up there to perform, you’re either good or no good. And if you don’t do it good, no matter how much money or power is behind you, it won’t happen. There was no bluff involved with ELP. It was a natural thing.

HP: Did things for Tarkus start to jell in the studio or on the road?

Greg: In the studio. I mean, not only in the studio. You don’t just walk in and start doing it. You work out for month-and-a-half, two months ... working through everything in a room. At that time we had awful troubles with rehearsal rooms. We got thrown out of them all. At one point we were practicing in a church hall, and keep in mind we were loud even in those days, and there was a guy who lived across the road a half-mile away who told the authorities that when he was taking a bath we had caused ripples and waves in the water. So we got tossed out of that place. Everything was largely organized in our own homes. Keith would come over to my house and sit down at the piano to work it through, or I would go over to his house...

HP: When did you begin to get used to criticism? ELP has never been adored by the press.

Greg: Very early, man. Our second date... I’ll tell you how it happened. We decided to play our first tour, after a lot of debate and discussion. And the first date we played was the Isle of Wight festival. 6,000,000 people showed up. It was absurd. We were a bit scared of that being our first show, so we did a little date before it. Sort of the way Crosby, Stills and Nash played a small college for their first show rather than Woodstock the next night.

Then we did the festival, and after that festival we got hammered in the press. They were waiting for us with polished teeth. And of course, they bit in deep, but we’d created enough interest by this time that the people would come to see us anyway. So on the tour, the shows were going down incredibly well and the press were saying ‘They’re nuts, they’re crazy’. One of the most famous remarks was made by the English disc-jockey John Peel. He said ‘They’re a waste of talent and electricity’.

HP: Is he a friend of the band's now?

Greg: No. No way. It hurt for a very long time, the criticism. But the more they layed [sic] into us, the more we stuck together. And we decided fairly early on that we would say nothing about it. We wouldn’t retaliate and we wouldn’t get bitter. To this day, we’ll say nothing about anything. We’re a very easy band to attack.

How easy it is to say 'Look at these fools ... and there’s an energy crisis going on!'? That was actually said last week in the Melody Maker, that we were a waste of power. But then you go to the people and you play to the people and they decide, man. They’re the heavyweights. Critics bands never make it. But although criticism never does anybody any good it doesn’t affect us anymore.

It does hurt personally. I mean when you know you’ve sweated your guts out for months and months and months and sat up all hours of the night. My bloody eyes have burned some nights, and then somebody will write the lyrics off in a sentence. That much thought, you know. That’s sad. But if I continue on this point, I’ll be doing exactly what I don’t want to do.

HP: When Brain Salad Surgery came out... the English press started to...

Greg: They started long before that.

HP: Why?

Greg: I don’t see why ... well, I do see why as a matter of fact. We haven’t been there in two years and we had nothing really to say to them. We weren’t doing anything in England, the most we could do with full confidence was release the records to give the people what we’d been creating. But we had very little to say interview-wise. We weren’t playing shows and we’re not the type of band that tries to do a story a week. ‘Get this paper one week, that one the next’. That just isn't the way we work. We’ve never worked through the media or the press.

We’ve always gone directly to the people. lf we’ve got a thing to do, we go to the people and do it. And then they decide whether it’s good or bad and the press just join in like a bunch of fools. Right now we’re gonna go back to England and play live days at Wembley and we’ll sell them out. And then we’ll release the album and it’ll go number one. And then what are they gonna say? Tell you what they’ll say. ‘Heros! They’ve come back!’ So what do you believe?

They’ll drive you mad in the end. It happened to Yes as well. They build you up, you know, and then you get to a place where you’re the least bit precarious and BANG! They let you have it. The next one I’m waiting for is for us to be ‘an imitation of ourselves.’ That’s got to be the next one. It’s been said about Mick Jagger, right? Mick Jagger’s trying to be Mick Jagger ... and all this bullshit. It’s just not that important. We’re lucky though, because a lot of bands do suffer by it. We don’t.

HP: Was Trilogy a difficult album to make?

Greg: It was a hard album to make because it was a very accurate album. A lot of time went into it, a lot of care. In many ways, it’s one of the best albums we’ve done. It’s hard to look back and talk about what you think of this one or what you think of that one, you know. They’re all one thing to me. If I go out there on stage tonight, I’m playing all of them. You may look at them as set with each one as a separate chronological development, but I’ve lived through all those so they’re all linked together.

At one time we may have just finished recording one album and yet on the side of that you’re probably writing something for the next record. It doesn’t come to a standstill. Never. People who listen to them listen to them when you want them to listen to them, so it’s a slightly different thing from my position. I must say that I do look back on Trilogy with a lot of respect. There’s some fine work on that album. I suppose that’s true with all our albums.

It freaks me out how many people say ‘Oooo, I wish I hadn’t made that album!’ Of course, once you’ve made it, there’s an anti-climax involved, but allowing for that I think I can still play the first album that we made and can still dig it. It doesn’t date. And that’s interesting if you get into it. I, in fact, still dig the first King Crimson album. That may date a little, but I’m still pleased with the way that turned out.

HP: I hear you’re on the verge of recording your first solo album.

Greg: I’ll make one this year. Principally, they’ll be acoustic tunes. It’s important that one understand the motive for making a solo album. It’s becoming a very trendy thing to do and I think generally for the wrong motives. Most cats out of bands made solo albums because they want to establish themselves. They’re a paranoid attempt to establish one’s identity. For me, that’s not the way I would make my album. I’ve made lots of the fuckers. There’s only so much room within a band which shares itself three ways. To exploit all that you create ... I can only do so many acoustic numbers with it becoming overbearing within the context of this show or this group or our albums.

I do some, usually about one song an album that’s totally acoustic. Things like “Lucky Man”, “From The Beginning” or “Still You Turn Me On.” The same as Keith will usually play one piano piece an album. The rest of it is a combination of the three of us. The reason I want to make a solo album is that I have a lot more things that I really want to play that are more acoustically inclined. But, of course, I can’t cut eight songs on an ELP album. That’s the reason I want to do it. I’m not doing it for the money. I don’t need to do it for the money. It may not even sell very well, although I have an inclination to think it will.

It’s just a thing where I’m not gonna tear-ass to do it. It’s a thing I suppose ... a lot of people ask me, you know, when it’s coming out, ‘When are you gonna do one?’ It’s a thing that I think people are gonna want to hear. It seems like the right time to do it. Whereas a year ago, it would have been the wrong time. I would have been promoting myself, if you know what I mean. I felt uncomfortable, plus there wasn’t a new ELP album. It’ll be good to do right now.

HP: The next album will be live, right?

Greg: Right. There are a few things that I really like about doing a live ELP album. This is the first truly Quadraphonic show to go on the road. And I think that’s a trip. If people are gonna have Quad players, and I’m told they are, I don’t see it. I don’t see them in people’s homes, but I’m told they are. And if they have got them, and they enjoy Quad, then one of the nicest ways to do it is to enjoy it in a live atmosphere. The beauty of Quad is that it’s four-dimensional. It surrounds you. The most suited thing is a live performance in Quad.

In many ways, it’s a lot better than a contrived recording where you put this sound in that corner. That’s obviously a trippy gimmick. A live album I would like to have out on ELP would be one where the audience would be on the back two speakers and the band in the front two. So when you listen to it. when you shut your eyes you’ll sit in the crowd and hear the band play. That would be a nice way to use Quad. That’s one of the things I like about doing a live LP.

The other thing is that he music we play off all the albums, we’ve changed it so much that it’s really nothing like it is on the recordings. So there’s some new things. The show has never been better than it is now and I don’t think we’ve ever played better than we’re playing now. It’s a good time to capture that on record and for anybody who’s into ELP and ELP’s music, it’s a nice album to have.

It’s probably the best things we have ever played and done when we’re performing well. I mean “Tarkus” is one of the best tracks we’ve ever had. So that’s gonna be on and “Take A Pebble”, from the first album, is one of the things that has lasted well for us. “Lucky Man”, “Hoedown”, “Trilogy” ... see, we haven’t heard the tapes yet in total. I’ve heard some of them and they’ve been really nice. Surprisingly good. I usually hear live recordings and just throw them away. They’re often a rip-off. But these are clear and present and they’re very live.

So the best of what we’ve done is there. If there is a whole show and it’s not too over-indulgent, there’s not too many lengthy solos and things so that people won’t get bored ...‘cause it’s all very well when you’re doing a visual thing, like Keith’s solos ... but then you can’t see them on record. It’s a different thing altogether. So obviously, these things have got to come out ... they’ve got to be presented in an exciting fashion. It’ll be a challenge, but I’m sure we can pull it off. If we could release a three record set of the whole show, I’d do it. And for a reduced price, too. Live albums cost nothing to record, so there’s no use in overcharging.